… and attention to detail.

Inherent objectification need not, of course, be reserved for males. We do it to our sisters, the minute we engage in comparison and competition centered on looks and/or seduction. We do it, if in position of some power, when choosing the portrayal of rented bodies or those observed in situ. There has been much debate about women photographers, for example, who are giants in their fields. The photographic morality of Diane Arbus, for one, was often questioned, when she chose to portray those living at the margins. She was accused of catering to our baser, voyeuristic instincts, to exploit our appetite for freaks. Sally Mann comes to my mind as well. There was much outcry over her photographic treatment of her own nude children, a debate that was only muted by the tragedy of Mann’s son’s suicide not 18 months ago. Wherever you come down on this debate, the possibility exists that gazing is not just a man’s domain.

How do we find a way, then, man or woman or those still differently assigned, to morally peruse the world?

There’re ways of looking at each other that are not objectifying.

Looking at a body scarred by cancer or following someone’s path through dying with the camera is an act of bravery, not objectification. This seems particularly true in our modern times, which makes it easy to avert your eyes from death. If we are facing now a rash of photographic documentation, from art forums to The New Yorker, it’s in long overdue reaction to that void.

If you watch someone, irrespective of their gender, to memorize the liveliness, the smile, the form, it is an act of wish or need to keep what mattered. If you look closely, with the goal to learn how someone moves, or what’s their mood in order to react accordingly, that’s not objectifying. And if you crave to let your eyes peruse all that the world provides because you do not know how long you can, that is an act of longing, not insulting.

A life of looking closely at the world.

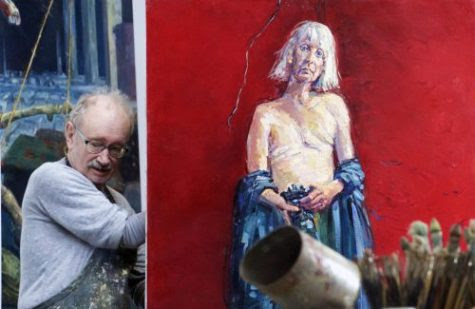

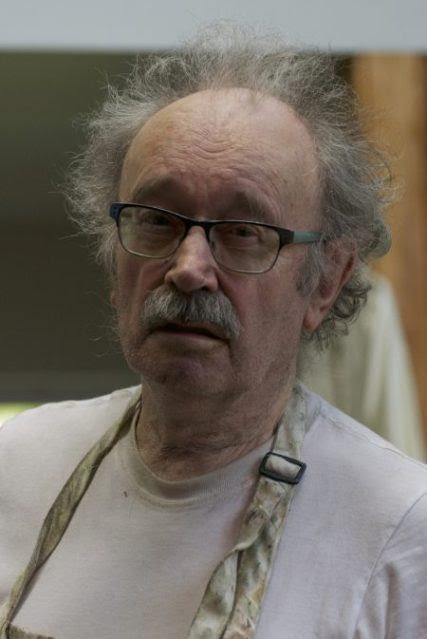

I’m used to looking closely at the world. These days it’s with the help of a third eye, my camera, which has become attached to me to document the world in which I live. I bring it to the sessions, at the beginning as insurance that potential gazes flow in both directions. Should I be object, I’ll be subject, too. As it so happens, that was never needed. The longish bouts in which the painter and this model lock their eyes are interrupted by the shutter click ensnaring bits and pieces of the process. My pictures represent the colors, the stance, the aging, lived-in face, while he’s at work. They tell of heightened concentration, a form of still abandon. They capture laughter, when we joke around the session, or frowns when we decry the fate of artists.

The artist is the subject is the artist.

The camera is her tool.

What they can’t show, these photographs, is how an act of unrestricted, mutual looking can bring about something essential. Each one of us documenting the other creates connectedness that voids any potential gaze. Not fraught with all the issues of the more familiar intimacy between lovers. No questions of the right or need to please, balance of power, possibility of loss.

This looking moves beyond the terms of object/subject and settles on the gift of being seen.

For the artist, every painting leaves its mark.

The completed portrait, in the studio. Henk Pander photo

Friderike Heuer

Portland, OR

November 2017