Beyoncé’s Pregnancy Photos Cast Her as a Venus for the Black Diaspora

Embracing and reinterpreting cultural traditions from which black people have historically been excluded, Awol Erizku reimagines Beyoncé into an idealization that has typically been reserved for white women.

Awol Erizku, photograph of Beyoncé (via beyonce.com)

Beyoncé’s announcement that she is pregnant with twins set the internet and social media on fire last week. The initial announcement — an Instagram post in which Beyoncé is dressed only in a bra, panties, and a veil — celebrates the singer’s pregnant form. By the following day, there was a full suite of photographs on Beyoncé’s website, mostly shot by Awol Erizku, an emerging artist best known for photographs of black models that reimagine paintings by European Old Masters like Johannes Vermeer and Leonardo da Vinci. Erizku’s photographs of Beyoncé are interspersed with family photos, including several of her with Jay-Z and their daughter Blue, underwater photos of Beyoncé taken by Daniela Vesco, as well as a poem written for the occasion by Warsan Shire, who provided text for Beyoncé’s Lemonade. Of these, Erizku’s photographs have gotten the most attention. One reason for this may be the way he has cast Beyoncé as a Venus for the black diaspora, a sexy and erudite celebrity and art aficionado.

Erizku and Beyoncé use the cosmopolitan strategy of embracing and reinterpreting cultural traditions, particularly those from which black people have historically been excluded, to reimagine Beyoncé into an idealization that has typically been reserved for white women. Beyoncé and Jay-Z are well-known art collectors, and they both reference art in their work. These photographs further demonstrate how adroit Beyoncé is in the art realm. In Erizku’s images, Beyoncé exudes self-confidence and cultural awareness by performing the conventions of the Old Masters as her own.

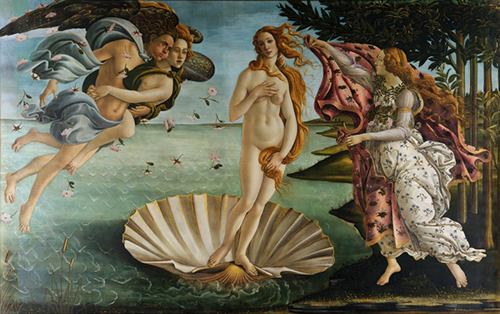

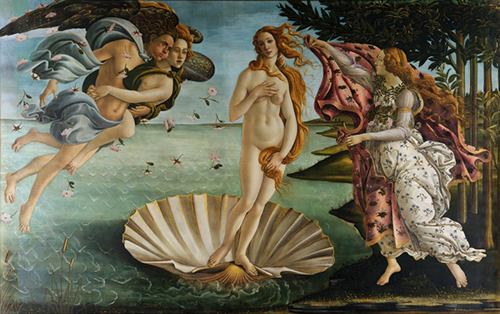

Erizku’s photographs refer to a long history of paintings of Venus. Reclining, Beyoncé resembles Giorgione’s “Sleeping Venus” (1508–10). Standing, she adopts the pose made famous by Botticelli’s “Birth of Venus” (c. 1482). Perhaps Botticelli borrowed this pose from the ancient Romans because it is erotically demure: Venus conceals her breasts and genitalia while drawing attention to the sensuous forms of her figure. The result is an idealized image of sexuality and sensuality with which artists continue to engage centuries later — something art historian Adrianna Campbell has suggested that Erizku is well aware of. But Erizku and Beyoncé have made one important change from most of their Old Master predecessors: In these photographs, rather than looking into the distance like Botticelli’s Venus, or having her eyes closed like Giorgione’s, Beyoncé is looking directly at the viewer, as if to acknowledge that she knows we feel compelled to look at her, perhaps out of desire or longing to be like her. As a result, she has the appearance of being largely in control of how we see her.

Botticelli, “Birth of Venus” (c. 1482)

Giorgione, “Sleeping Venus” (1508–10)

Black artists have been making use of the conventions of Old Master paintings to reimagine blackness for the past fifty years. Erizku follows Romare Bearden, whose collages universalize the beauty of black women; Emma Amos, whose paintings of black women present a direct challenge to standards of beauty throughout the history of European art; Robert Colescott, who reworked themes from the Old Masters to address contemporary assumptions about the interrelatedness of beauty, sexuality, and race; Renee Cox, who recreated Leonardo’s “Last Supper” to incorporate her own nude body in the place of Christ in order to assert her agency within the history of art; and Kerry James Marshall, who questions the conventions of European paintings while also using them to assert the beauty of black women. More recent predecessors for Erizku’s Beyoncé photos include Kehinde Wiley, who in 2012 began painting black women in poses from Old Master paintings to correct their historical exclusion from the canon of beauty, and Mickalene Thomas, who recreates European paintings to represent black women as agents of self-representation. These artists have wrested the conventions of beauty from the hands of white artists and made them their own in order to tell new and complex stories about race, fashion, elegance, class, and sexuality.

Mickalene Thomas, “A Little Taste Outside of Love” (2007), acrylic, enamel, and rhinestones on wood panel, 108 × 144 in. (courtesy of Brooklyn Museum)

Mickalene Thomas, “A Little Taste Outside of Love” (2007), acrylic, enamel, and rhinestones on wood panel, 108 × 144 in. (courtesy of Brooklyn Museum)

Erizku’s Beyoncé photographs are perhaps most like Thomas’ paintings of black women, which use poses from the paintings of Edouard Manet, Gustave Courbet, and other European artists, but with an important difference: Whereas Thomas reworks her art-historical references to establish distance between model and viewer, Erizku’s use of Old Master conventions make his photographs of Beyoncé appear more inviting. Thomas often selects erotically charged poses, including Courbet’s “L’Origine du monde” (1866), but, as if to thwart the sexual availability the poses suggest, she makes sharply focused photographs with saturated colors and paints on board in glossy enamels adorned with sequins, giving her works a hard and almost impenetrable surface that serves as an allegory for her models’ self-conscious autonomy. By contrast, the soft focus and pastel colors of Erizku’s photographs represent Beyoncé’s skin with a lush and inviting sensuality while also evoking the sentimentality appropriate for a pregnancy announcement.

Awol Erizku, photograph of Beyoncé (image via beyonce.com)

Erizku complicates his images by mixing the inviting sexuality of Venus with references to traditional paintings of the Virgin Mary, as culture writer Constance Grady pointed out on Vox. For example, Mary’s blue mantle or cloak is evoked by the veil and blue silk panties Beyoncé wears in the first of the photographs released on Instagram. Shire’s poem accompanying the photos refers to Beyoncé as a syncretism of “mother turning into Venus,” and also imagines that as she gives birth, she is joined by Nefertiti, the Egyptian queen, and by Osun and Yemoja, Yoruba deities Beyoncé has referenced before who are already linked with Mary in religious traditions of the African diaspora. Appropriating and commingling these traditions is a diasporic strategy signaling cultural adaptation and resilience in a society that marginalizes black people.

As America awakens to the deliberate philistinism of a Trump White House and a Republican Congress, the beauty, cosmopolitan erudition, and staggering popularity of Erizku and Beyoncé’s diaspora Venus — which set a world record for “Most Liked Image on Instagram” — speaks to black artists’ increasing cultural power in the public sphere, a place where #QueenBey may be more adept than anyone at navigating the intersection of art, taste, and fashion.