When a Grecian Urn Takes a Step Onto the Cosmic Banana Peel

When a Grecian Urn Takes a Step Onto the Cosmic Banana Peel One afternoon not too long ago, a truck arrived on Park Avenue, delivering a batch of Impressionist paintings from a family’s home in the Hamptons to their apartment in Manhattan. With some but not all of the art unpacked, the lady and man of the house went out for the evening, leaving instructions for their maid to finish up and get rid of the boxes.

She put the paintings in the bedroom, and took the boxes out to the service entrance of the building.

In the morning, as the owners began to get the art ready for the walls, they realized that they were short four paintings. “They scrambled around the next day, looking everywhere,” said Colin Quinn, director of claims management in the United States for Axa Art Insurance. “At the end of the day, they reported it to us.”

The maid had worked for the family for more than 10 years and was above suspicion, Mr. Quinn said. The conclusion was that the paintings, still in their crates, had ended up in the trash, he said. They were long gone by the time the insurance investigators arrived.

“These are the ‘oops’ claims,” Mr. Quinn said.

On Friday, a woman taking a class at the Metropolitan Museum of Art stumbled into “The Actor,” a work by Picasso dating to 1904 or 1905. The canvas was ripped in the lower right-hand corner.

New York is like many big, crowded cities in having plenty of art to bump into — or drop or toss in the trash or surrender to the cosmic banana peel. A drawing by Lucian Freud valued at more than $100,000 was accidentally put through a shredder by Sotheby’s in London in 2000. A man tripped over his shoelace on a staircase at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, England, and managed to shatter three Qing dynasty porcelain vases, as The Guardian reported.

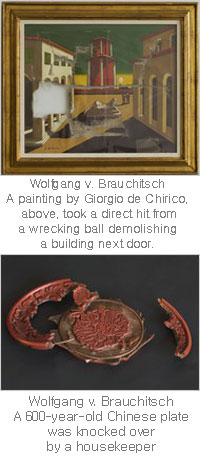

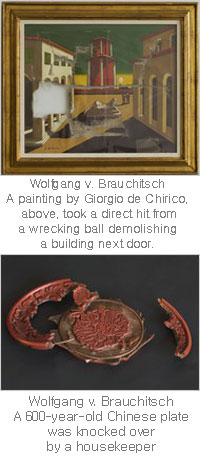

There’s more. A painting by Giorgio de Chirico, “Piazza d’Italia,” was hanging on the wall of a townhouse in the Netherlands when demolition began on a bank next door. The wrecking ball came through the wall of the house and shot a perfect hole through the canvas. In Germany, a Ming dynasty lacquer plate — about 600 years old — was hit by a housekeeper’s elbow and ended up in bits on the ground. These two items were soberly displayed by Axa Art at the 2009 Art Basel exhibition in Switzerland under the caption “The Thrill of Protecting,” although it might as well have said, “Let This be a Lesson to You.”

Representatives of New York’s leading museums say collisions between visitors and art are rare, and none of them were inclined to steal the spotlight from the mishap at the Met by talking about them.

“Incidents happen,” said a spokeswoman for Museum of Modern Art. “There are no incidents we can discuss in the press.” The Whitney didn’t “have anything to contribute,” a spokesman said. At the Frick Collection, there has been “no apples-to-apples incident” comparable to the damaged Picasso, said Heidi Rosenau, a spokeswoman.

All of the big institutions have strategies to keep people at a safe distance from the artwork — seeing-eye alarms triggered when someone leans over a rope barrier, or guards who keep their eyes fresh by frequent shifts from one gallery to the next.

Compared with some of the bigger museums, the Frick, housed in a mansion on Fifth Avenue built by Henry Clay Frick, is a remarkably calm setting. That serenity is aggressively protected: Children under age 10 are not admitted.

“It’s a longstanding rule related to the fact that we have a minimal number of stanchions for displays,” Ms. Rosenau said. “Things are not in glass cases to a great extent. This was the house of a private collector, not a big institution.”

Art catastrophes can happen anywhere. One night at Tavern on the Green in 1995, Jean Kennedy Smith, then the American ambassador to Ireland, was being honored by Irish America magazine for her work bringing about a cease-fire in Northern Ireland. To commemorate the event, a piece of Waterford crystal was carved in the shape of an American flag with eagles. It was a big, glittering hunk of glass that would be presented by the master of ceremonies, Donald Keough, an investment banker.

But before Mr. Keough or anyone else could get their hands on the crystal, another speaker heading for the podium brushed past the sculpture. It toppled off the back of the stage.

Mr. Keough looked down at the remains and took a deep breath.

“Madam Ambassador,” he announced, “you’re going to receive more pieces of Irish crystal than anyone in history.”

When a Grecian Urn Takes a Step Onto the Cosmic Banana Peel

When a Grecian Urn Takes a Step Onto the Cosmic Banana Peel